Q+A with Edward Snowden’s Chief Legal Advisor Reveals the Free Speech Glass is Half Full, Even in the Post-9/11 World

The following is based on a conversation between American INSIGHT and Ben Wizner, ACLU Director of the Speech, Privacy and Technology Project and Chief Legal Advisor to Edward Snowden, via Skype video call on November 1st, 2017. With Mr. Wizner’s approval, his responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Ben Wizner, ACLU Director of the Speech, Privacy and Technology Project and chief legal advisor to Edward Snowden, says the only title he’s ever wanted is ‘ACLU Lawyer.’

You’re a busy man, Ben. Where are you most likely to be when someone asks you what you do, and how do you answer the question we all dread, “Tell me about yourself”?

I spend most of my waking hours at work, just like all of us who work for a living, either unglamorously sitting at my desk scrolling through Tweets and deleting email, or traveling around the country and the world to talk about the ACLU.

At its core, what I do is about trying to defend liberal and free societies from various kinds of encroachments. If I’m in Germany, I say I’m a human rights lawyer. If I’m in New York, I’m a civil rights lawyer. If I’m in Washington DC, I’m a civil liberties lawyer. To me those terms are interchangeable. But the only professional title I’ve ever wanted is ‘ACLU Lawyer.’

Who are the role models that inspired you to defend Freedom of Speech and human rights?

I’ve had great role models along the way. They include people like Bryan Stevenson, who runs the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama, who is one of the great public interest lawyers of our time, if not the greatest, and who was a mentor to me in law school. And then I would say the stories of lots of people I have never met, and seeing that even small groups of people can make a significant impact on the world.

In an interview with Forbes you said prior to your work with Edward Snowden you had spent 10 years trying to bring lawsuits against the intelligence community. What is your ultimate goal as an attorney?

Wizner spent the immediate post-9/11 years engulfed in battles against the intelligence community, a group he says is largely untouchable.

At the highest level, it’s to advance liberty, equality and fairness. But that means very different things in very different contexts.

There was a period of a decade where trying to bring litigation after 9/11 and our government’s severe overreaction to it, did not comprise lawsuits we were likely to win in court. It was almost impossible to sue senior leaders of the intelligence community because of all the barriers to accountability. In that context I would say at a minimum we’re bearing witness and creating a formal record of this period, of how the country went astray.

But we are also litigating in the court of public opinion, setting up these cases in a way that will make people think harder about human rights in an age of terrorism. We want to change the question from “what rights should terrorists have,” which most people will answer none, to “what happens when we abandon the Rule of Law?”

How do you win a case in the court of public opinion?

Let’s say you oppose torture in all circumstances, as I do. You think it’s equally a crime if it happens to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged 9/11 mastermind, or my client the German citizen Khalid El-Masri, who was mistakenly kidnapped by the CIA and tortured. The public will react to those two cases very differently. So if you’re deciding who to represent in a major case, it might make more sense to represent the person who’s unquestionably innocent. It’s a way of getting the public past those initial barriers, to considering the interplay of terrorism and human rights. You have to choose the plaintiffs carefully, tell the story in a compelling way, and include your clients’ voices in a prominent way. These are the basic ingredients to winning a case in the court of public opinion.

Do you tell these clients up front that they probably won’t win their case in court, and at best might win in the court of public opinion?

Of course. I think it would be unethical not to. The goal here is not always just individual justice for one person, but to change the practice so that other people won’t suffer from it.

Now, we do have to determine with clients whether it makes sense for them to participate on those terms. The experience itself might be too re-traumatizing. Imagine that you are an unacknowledged victim of the US torture regime, and the US response to your lawsuit is to declare that the subject matter is a state secret, and that the case has to be dismissed. It takes a lot of fortitude, and a lot of honesty to go through with something like that.

You probably won’t be surprised to hear that almost all the victims of these practices are enthusiastic about participating in these cases, with the full understanding that they’re unlikely to win in legal terms.

Considering your career progression from radical college student, to Director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project, to Edward Snowden’s chief legal advisor, what does the concept of Freedom of Speech mean to you now?

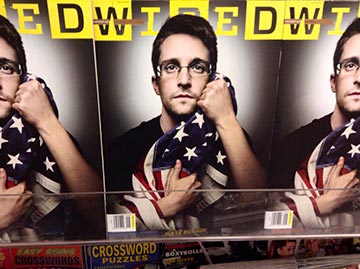

Since 2013, Wizner has been the principal legal advisor to NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden.

When I was a radical college student, I thought of the kinds of issues that the ACLU works on, like Freedom of Speech, as being mostly established liberal rights that didn’t need a lot of tending too. That our focus needed to be pushing the country to deal with the grotesque economic inequality it faces. The Bush administration’s response to 9/11 made these core, established rights vital and radical again.

Pre-9/11, the picture we had in our heads of Freedom of Speech was a bunch of people holding signs and trying to get a parade permit. In practice, after 9/11 we saw that federal law enforcement was going after people for their views, without saying that’s what they were doing.

Freedom of Speech and association were so constrained for certain communities, particularly South Asian and Muslim Arab communities, by the ridiculous prosecutions for “material support for terrorism,” – like supporting Palestinian rights in a particular way; or giving to a charity that was trying to help refugee children, whose only way to help those children in certain regions was to work through entities that were subsequently designated terrorist organizations by the USA; or the unbelievably intrusive surveillance into local Muslim populations where people had to assume that any new worshiper in their mosque was an undercover agent – this idea that you could split of Freedom of Speech from other core civil rights was revealed to be false.

When we look at the history of Freedom of Speech, we see that the concept has crossed several critical junctures, arguably beginning with the Magna Carta, and progressing to the UN Declaration of Human Rights. Are we in the midst of another critical juncture in the history of Freedom of Speech?

It’s a fair question, and it certainly has seemed that way within the ACLU. Tensions and conflicts have emerged in progressive communities about whether all speech needs to be defended, even when it’s speech by deplorable racists and white supremacists. Events like the tragedy in Charlottesville have resulted in a lot of anguish and soul searching among people, even in the Free Expression community.

Are people suggesting that Free Speech is not worth defending anymore?

People are talking about it in two ways.

One is the question of resources – why should an organization like the ACLU devote any of its resources to defending deplorable speech?

The second question is more on the level of political philosophy – do we need to incorporate some sort of power analysis into our understanding of Free Speech, that would allow us to apply not necessarily consistent rules and account for who the speakers are, and their relevant power position in society? It gets into a very difficult line drawing, but who would be doing that line drawing?

Well what about you, do you still think all speech is worth defending?

I think the fact that Jeff Sessions is the Attorney General, and Donald Trump is the President, is precisely the reason why we have to be even more vigilant in defending Freedom of Speech.

When Jeff Sessions thinks about hate speech, he’s not thinking about the KKK, he’s thinking about Black Lives Matter. And you’ve already seen lawsuits brought against BLM for inciting violence. So if we start carving out exceptions for what people call hate speech, I would say that I think any efforts to create a legal regime that would prohibit or punish that kind of speech, are likely to create a cure that is more harmful than the disease.

And I mean that even in regards to progressive movements for civil rights. The people who would be hurt the most by a regime that creates categories of acceptable and unacceptable speech are the people who are pushing for progressive social change. The students at Berkeley might feel like they’re the side that has power because they’re in a liberal institution, but the rules we make will also apply to sheriffs in Alabama, not just the provost at Berkeley. And so I would say that strong First Amendment protections have been vital to every movement for social change in this country’s history. Had people in authority been able to suppress speech on the grounds that it was offensive or hateful, they would’ve used that to crush progressive movements.

What’s your advice to somebody on the other end of hate speech?

I don’t think they need my advice. But I do think we need to acknowledge that words injure. The childhood rhyme about sticks and stones is nonsense. Words are powerful. If they weren’t so powerful, they wouldn’t be so worth defending. So I cringe when people say that people on the receiving end of hate speech “just need to toughen up and have thicker skin.” It’s not for us to say that.

What are your hopes and fears for the future of Freedom of Speech?

We’re seeing very illiberal winds blowing around the world. There seems to be a deep hostility toward liberal principles, and that’s a global trend. That’s very worrying. At the same time, the generation that is emerging now is extremely engaged, and politically active. And that’s a cause for optimism. Even if I don’t agree with all the activism going on right now, I’d rather see people be passionate for social change than apathetic and focused on their own lives.

So are you saying that the future bright or bleak?

It’s both! Always! While we’re invariably losing cases in one area, we’re also invariably winning cases in another, and moving things forward. Even when the Bush administration was engaged in awful human rights abuses based on national security policies, we were making historic progress in marriage equality and women’s rights.

There’s always going to be reasons for pessimism and optimism. The glass is always half full and half empty. But the question we always need to ask ourselves is what would it be like if all of us who worked for social change stopped doing it. If we entirely removed ourselves from the equation. It’s pretty clear things would be a lot worse for a lot more people. And that’s all the motivation I need.

Readers are invited to meet Ben Wizner at the 2017 Free Speech Award Ceremony on December 6th in Philadelphia. Tickets on sale now! Limited seating available. To purchase tickets, visit www.freespeechfilmfestival.com!