Pace of voter registration purges accelerate; Georgia and Wisconsin cut 500,000 from rolls

The names of more than 500,000 voters—more than a half million, in two states—were deleted from voter registration rolls in a four-day period in December.

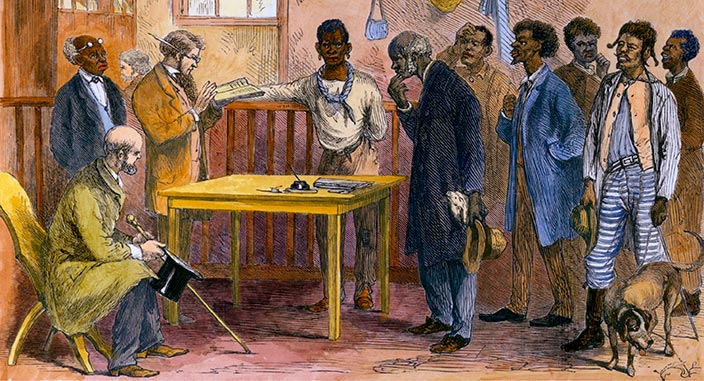

More than 50 years after passage of the Civil Rights Voting Act of 1965, the war to protect voting rights is still being fought across the nation—and the outcomes of these battles and skirmishes could affect who gets to vote and who doesn’t in the 2020 presidential election.

The pace of large-scale purging of voters lists has accelerated since 2013, when the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated parts of the Voting Rights Act. The Court’s Shelby County v Holder decision loosened federal supervision of states with a history of voter suppression.

Overall, 17 million voters were purged from voting rolls in the U.S. between 2016 and 2018.

The Brennan Center for Justice, a policy and research organization that monitors voting restrictions, says states have introduced hundreds of “harsh measures making it harder to vote.” Besides voter roll purges, tactics include photo ID requirements, elimination or curbing early voting, and closing of polling places. Civil rights activists contend these strategies particularly affect people of color, the poor and young people—citizens who tend to vote for Democrats.

“Purging, if done wrong, can disenfranchise eligible Americans,” says Myrna Pérez, director of the Brennan Center’s Voting Rights and Elections Program. “And purges are happening at a scarily high rate.”

All these tactics were in play in the 2018 gubernatorial race in Georgia, in which Democrat Stacey Abrams lost by 54,723 votes to Republican Brian Kemp. As Georgia’s Secretary of State, Kemp supervised voter registration. A year before the election, his agency purged more than 500,000 voters. He refused to step away from that responsibility during the campaign.

Free Speech award-winning film spotlights Georgia

The Georgia race is examined in depth in SUPPRESSED: The Fight to Vote, winner of the 2019 Free Speech Film Festival Award. The film, by Brave New Films, documents the obstacles Georgia voters faced. Besides purges, they included closing longtime polling places, missing absentee ballots, extremely long wait times, and a host of voter ID issues.

“The determination of many voters was inspiring, but still many failed to overcome the roadblocks placed before them,” said Director Robert Greenwald, founder and president of Brave New Films. “ No voter in this country should accept this. Voting is our fundamental right.”

Stacey Abrams founded Fair Fight Action

After her loss in the governor’s race, Abrams founded Fair Fight Action, a voting rights organization that’s spearheading action in 20 states to protect voting rights. Urged to run for one of Georgia’s two open Senate seats, Abrams declined, saying that voter suppression is the most pressing problem threatening democracy. “This is about whether voters’ voices can be heard; it’s about whether citizens are allowed to be voters.”

Fair Fight Action has challenged the Dec. 17 ruling by a federal judge that Georgia officials could purge 309,000 voters because they were assumed to have died, moved out of state, or had failed to vote since 2012. About 120,000 of those to be deleted haven’t moved or died, they simply haven’t voted recently.

“Georgians should not lose their right to vote simply because they have not expressed that right in recent elections,” said Lauren Groh-Wargo, CEO of Fair Fight Action.

Wisconsin voters purged ahead of 2020 election

In Wisconsin, a state judge on Dec. 13 ordered the immediate removal of 234,000 registered voters because they hadn’t responded within 30 days to a letter asking if they had moved. The state Attorney General and the bi-partisan Elections Commission both have appealed the ruling, and the Wisconsin League of Women Voters is trying to join their appeal.

Wisconsin has consistently voted, over decades, for Democrats in presidential races. But in 2016, Donald Trump eked out a victory of fewer than 23,000 votes over Hillary Clinton. He got the state’s votes in the Electoral College, votes that were critical for his election. Wisconsin voters can expect intense attention from candidates in the 2020 election, as the two parties scramble for the state’s votes.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that more than half the mailings (55 percent) went to districts that supported Hillary Clinton. Some of the highest concentrations of the purge letters went to Milwaukee and Madison, Democratic strongholds. The two cities account for 14 percent of Wisconsin’s registered voters but received 23 percent of the letters.

A conservative group prompted the Wisconsin ruling requiring the immediate removal of voters. The Elections Commission had planned to remove them within 18 months.

Activists in San Francisco protest voter suppression

States get aggressive about culling voters

Advocates of the purges in Georgia and Wisconsin say they were just a matter of “cleaning up” voters lists by getting rid of people who had died, moved or not voted in recent elections. Flagging voters who have died or moved is a legitimate way to cut election costs; contention arises when people who may still be eligible but simply haven’t voted recently, are purged.

States are culling their voters list more aggressively since the 2013 Supreme Court ruling that ended closer scrutiny of states with a history of voter discrimination, says Pérez, of the Brennan Center. Georgia, for example deleted the registration 1.5 million voters between the 2012 and the 2016 elections—double the number cut between 2008 and 2012.

In a study released in August, the Brennan Center found the median purge rate over the 2016 to 2018 period in jurisdictions previously covered by the Shelby County ruling was 40 percent higher than in jurisdictions that hadn’t been subject to tighter supervision. That worries Pérez.

“Are there systematic large-scale purges that are happening with sloppy data, without public notice, too close to an election and without a mechanism for correcting it if there were mistakes?”

And there are large scale mistakes. In Ohio’s attempt to eliminate 235,000 voters in October, almost 20 percent—about 40,000 people—were erroneously marked for removal. One of those was the executive director of the League of Women Voters, who job is fighting voter suppression.

People who are mistakenly removed from the voting rolls can re-register. Joel Kaul, Wisconsin’s State Attorney General, says that’s a poor solution.

“Any time people have to go through extra steps to vote, and certainly re-registering is a significant additional step, the result is that fewer people end up voting,” he said.

Susan Caba is an independent journalist who covered federal and Common Pleas Courts for the Philadelphia Inquirer. She is the author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Leadership, Fast Track, and writes about politics, popular culture and leadership.