“No law except the Putin Law” – Carole Keeney Harrington Discusses Pussy Riot’s Attempt to Bring Free Speech to Russia and the Making of Her Film, Pussy Riot: The Movement

Moscow is the archetypal Russian community. Beautiful people traverse magnificent architecture as they go about their daily business, each step taking them on a journey through centuries of history.

Moscow is the archetypal Russian community. Beautiful people traverse magnificent architecture as they go about their daily business, each step taking them on a journey through centuries of history.

Under the surface, however, Moscow’s splendor is overcast with an unforgiving, distant demeanor and a dark past dominated by violence, patriarchy, and oppression. Carole Keeney Harrington, after her experiences writing and producing Pussy Riot: The Movement surmises, ”Russia is full of brilliantly intelligent and breathtakingly beautiful people, but the Russian people simply don’t know how to be free.”

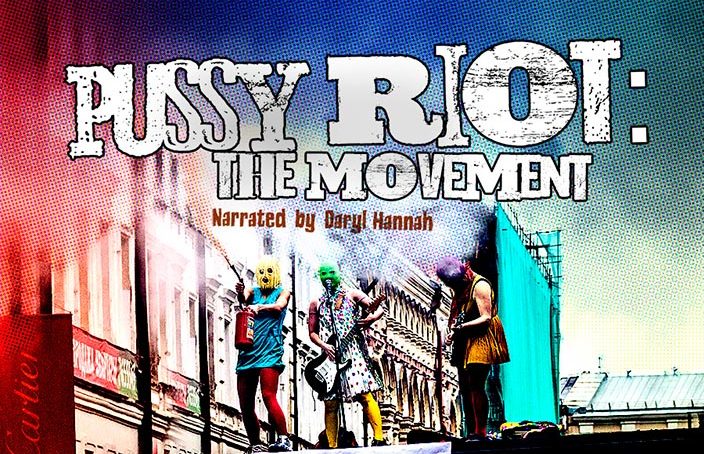

Harrington’s film Pussy Riot: The Movement traces the complete history of the band Pussy Riot, a feminist punk-rock group that rose to international fame on February 21, 2012 when six members were arrested for an impromptu performance on the steps of Moscow’s grand cathedral. She says the goal of Pussy Riot: The Movement was to discover why Pussy Riot arose when they did and how they became internationally icons, and to use the answers to these questions as a means for understanding why the Russian people tolerate the dictatorship of Vladimir Putin while their Constitution is completely ignored.

In a rigid culture dictated by obedience and order, Pussy Riot’s attire alone was enough to cause a national frenzy. Sporting combat boots with electric-colored tights only partially concealed by ¾ length dresses, all 11 members of the group stood bare-armed in freezing temperatures, hiding their identities behind brightly colored ski-masks. Add in electric guitars, rough amplifiers, and punk-rock vocals, and Pussy Riot’s chaotic presentation reflected its intention to uproot every single aspect of Russian society.

Director Natasha Fissiak (left) and Writer/Producer Carole Keeney Harrington (right).

One of those most attracted to Pussy Riot’s aura was director Natasha Fissiak. A Houston resident with Russian roots, Harrington says it was Fissiak’s visit to her Moscow birthplace during the criminal trial of Pussy Riot that inspired the duo to trace the band’s story from start to finish.

Having lived in the United States since the age of 14, Fissiak had become accustomed to the rights and freedoms granted by the American constitution. She had grown to know a legal system that provided what citizens were promised. Historically apolitical to Russian politics, Pussy Riot’s imprisonment moved Fissiak to document this revolutionary attempt at bringing Free Speech and the Rule of Law to her homeland.

Passionate and determined but without the tremendous resources involved in making a film, director Natasha Fissiak and producer Carole Harrington relied on investors’ passion for Freedom of Speech to fund the project. After a number of solid contributions, the team was ready to set out for Moscow, but not before a string of fortunate events put them in contact with some of Pussy Riot’s closest friends and acquaintances.

Natasha Fissiak, director, with Pussy Riot members Nadia Tolokonnikova and Masha Alyokhina after their early release from prison.

Harrington and Fissiak had funds, a crew, an extensive network of contacts, and the drive to make a film they considered crucial to the pursuit of Free Speech and the Rule of Law. But immediately upon arrival in Russia, the duo found the task they set for themselves would be an arduous one.

Natasha Fissiak arrived at the Sheremetyevo International Airport with three empty hard drives ready to be loaded with footage of a Russian society upended by the trial of Pussy Riot and the protests of Putin’s rigged re-election. The Russian authorities wasted no time in calling into question Harrington and Fissiak’s intensions. Where were they going? Why were they there? What was the film equipment for? What was the purpose of having three hard drives? After dozens of questions, the crew were allowed to keep their equipment, but their troubles were far from over.

The team rented two apartments in Moscow, both of which lie in close proximity to the infamous Red Square. Harrington describes two hoarse old women who could be found all day everyday sitting emotionless in a park across from the apartment nearer to the Red Square. The old women watched the crew with seedy, accusing eyes each time they entered or exited the apartment, especially when they brought guests.

After a number of days under the constant watch of the two women, the local police force phoned the crew to inform them that their apartment lie on a special road, a road that “important people” travelled on a daily basis. A few days later, officers showed up and accused the crew of “disturbing the peace.” Forced to abandon the first apartment, all operations were moved to the second apartment.

Natasha with Yekaterina Samutsevich, the third Pussy Riot member who was released early.

Through all the unrest, none of the crew was ever implicated. But Harrington makes it clear that while she knew she was protected by her American passport, the Russian members of the crew were overcome with anxiety. Harrington recounts all the crew agreeing at the start of filming to, “do as the Russians do: never share with others anything you don’t have to.” Harrington says no one in Russia knew what they were up to other than those directly involved.

“Do as the Russians do: do not share anything with others you don’t have to.” Harrington asserts this is a staple by which Russians go about their daily business, especially when it comes to the media. Harrington attests that the government controls all of Russia’s communications and that even across the 9 time zones the country encompasses, most people do not receive communication other than through state newspapers, television, and radio. For this reason, a large majority of Russians saw Pussy Riot as nothing more than a group of feminist hooligans. In fact, many of those who did support Pussy Riot, as well as those who protested Putin’s re-election, were arrested on charges of “hooliganism.”

Pussy Riot unleashed a social earthquake on Russia. But did they succeed in their goal? Harrington declares that if Pussy Riot’s ultimate goal was to change Russia’s legal and political systems, then the group was a complete failure just as every like-minded group has been and will be as long as Putin is in power. She says what Pussy Riot did do, however, was “raise a red flag to an already suspicious world that Vladimir Putin is indeed a dictator.”

Since the imprisonment of the six Pussy Riot members, the group has fallen off the radar both domestically and internationally. Harrington says that if Pussy Riot failed, no one group can succeed in overthrowing Russia’s legal and political systems alone. She says in order for change to come, Russians must overcome the mentality that only leaders create change. They must realize that the people can bring change themselves by rallying around groups like Pussy Riot. She says for now, though, Russians are too used to a patriarchal system, “they simply don’t know how to be free.”

Harrington affirms that Free Speech and the Rule of Law do not exist in Putin’s Russia. “There’s no law except the Putin law.”