Fighting for Free Speech in World War I: Eugene Debs on the Homefront

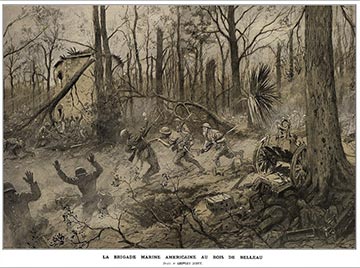

The year is 1918, and May has fed into June in the Belleau Wood near the Marne River in France. The lush green forest here rolls with hills steep enough for sledding in the winter but gradual enough to scale for a Sunday afternoon picnic overlooking the magnificent countryside. Amidst the centuries-old pine, oak, birch, and chestnut trees stand square brick stables groped by relentless vines that seem to grow in every direction. Equidistant from Paris and Calais, one can be at either city on horseback within just a few hours.

“La Brigade Marine Americaine au Bois de Belleau” by Georges Scott

The beasts go about their business uninhibited; their owners have fled West to escape the invading German army. It is here that the wearied German army, exhausted from three years of trench warfare yet still intent on forcing its opponents into surrender, is about to launch one of its final offenses into France before the fresh American troops, who are arriving ten-thousand by the day, can reach the battlefield.

Back in the United States, Congress is a year removed from their 1917 declaration of war on Germany and its allies. The Boston Red Sox have just begun what will be their only World Series Championship season of the 20th century. The US Postal Service has recently become the first mail service in the world to extend its operations to the skies. Plastic shopping bags have just gone into use in grocery stores.

Woodrow Wilson is President, and the draft has gone into full effect. 2.8 million men have been conscripted to fight in Europe’s war, chosen at random by local draft boards who select draft numbers blindfolded out of a fish bowl or top-hat. The entire American economy has been mobilized to produce the soldiers, food, weapons and ammunitions necessary to have an impact on the battlefield.

To ensure full support for the war, Congress has passed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, efforts undertaken with the intention of punishing anyone who expresses doubt about America’s involvement in the conflict. Patriotic groups like the American Protective League work with the FBI to identify anti-war expressions made by individuals or groups.

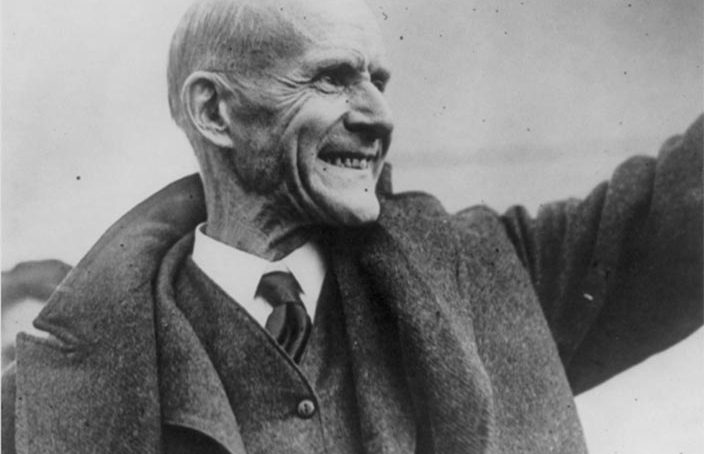

Eugene Debs delivering his address at Canton, Ohio in June of 1918.

One of the loudest voices of this period is Eugene Debs, outspoken proponent of labor unions and leader of the Socialist Party. Labeled a “traitor” by the Wilson administration, Debs takes the stand at Nimissila Park in Canton, Ohio. Before him stands a crowd of hundreds of anti-war protestors. Debs knows that he can, and probably will, be arrested for the comments he is about to make. However the self-proclaimed orator has made a name for himself by speaking out against injustice. He will not be silenced by anyone, not even his government.

A founding member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, the American Railway Union, and the Industrial Workers of the World, Debs’ life is dedicated to fighting back against the exploitation attempts of those in power. After one year of American involvement in World War I, Eugene Debs has taken it upon himself to publicly express his disillusionment with a war he claims does not benefit the average working American, even if that means landing in jail.

“I realize that, in speaking to you this afternoon, there are certain limitations placed upon the right of Free Speech. I must be exceedingly careful, prudent, as to what I say, and even more careful and prudent as to how I say it. I may not be able to say all I think; but I am not going to say anything that I do not think. I would rather a thousand times be a free soul in jail than to be a sycophant and coward in the streets.”

Speaking at Nimisilla Park, Debs has chosen a symbolic location. The park sits in close proximity to the jail where his three friends Charles Ruthenberg, Charles Baker, and Alfred Wagenknecht are being held on charges of espionage.

In his speech, Debs points to a contrast between America’s reason for going to war and its conduct at home. On the home front, opponents of the war have their Freedom of Speech limited by both the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. Abroad, however, America claims to be fighting for the preservation of liberal democracy. Debs is convinced, based on this dichotomy, that the war is being fought for Wall Street plunderers.

“Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder. In the Middle Ages when the feudal lords concluded to enlarge their domains, to increase their power, their prestige and their wealth, they declared war upon one another. But they themselves did not go to war any more than the modern feudal lords, the barons of Wall Street, go to war.”

Debs has made similar speeches before, but this one stands out because it is the first time a stenographer is present. The stenographer is an employee of Northern Ohio district attorney Edwin S. Wertz. Wertz knows if he can get Debs’ statement copied word for word, he can present a sedition case against him.

Debs never directly told his audience to avoid the draft. Nevertheless, Wertz has him arrested for three counts of espionage on the basis that he represented a threat against the USA by encouraging Americans to be disloyal. His sentence is ten years in prison and disenfranchisement for life.

Believing his Freedom of Speech to have been abridged, Debs takes his case all the way to the Supreme Court.

Eugene Debs vs. USA has become one of the most well-known, and controversial, Supreme Court cases in American history. In his defense, Debs argued for complete Freedom of Speech under the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. A judgment against him, he said, would be a judgment against to one of the country’s most sacred Freedoms. The Supreme Court, however, cited numerous anti-war statements made by Debs. In particular they pointed to Debs’ defense of draft defectors who had been imprisoned. His conviction was ultimately upheld.

The story does not end there, however. In 1920 Debs ran for President of the US from inside his jail cell. He would receive nearly 4% of the popular vote, the most ever for a self-proclaimed Socialist. In 1921, Congress repealed the Espionage and Sedition Acts, and President Warren G. Harding commuted Debs’ sentence to time served. The two met at the White House the day after Debs was released.

Eugene Debs vs. USA stands as one of three instances in 1919 when the United States Supreme Court ruled against Freedom of Speech. The orator and political figurehead remains a controversial figure in American history. Some still say obstructing a war effort deserves imprisonment. Others argue for complete, uninhibited Freedom of Speech. There will undoubtedly be future Eugene Debs that emerge during American wartime. Only time will tell if they too have their Freedom of Speech abridged.

Additional Materials

Eugene Debs speech at Supreme Court

Mark Ruffalo covers a portion of the Canton, Ohio speech: