Art by Child Detainees Depicts Stark Conditions

By Susan Caba

When 8-year-old Arthur Towata was ushered into Manzanar with his mother and 2-year-old brother, all he saw was black—black tar-paper covering the barracks of the internment camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II.

For years, Towata resisted the pleas of elders to memorialize his three years in the camp. “The Japanese push aside unpleasantness and try to make the best of circumstances,” he said, explaining his reluctance. But his experience at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, in an arid part of California, was seared into his memory.

Six decades later, by then a well-known ceramic artist, Towata returned to Manzanar for the first time. Placing one of his pots—organic and earthy—on the ground, he realized how much his experience there had influenced his work. He began to paint, to express those memories in ghostly paintings on tar-paper-black canvas and called them “The Black Wall Series.”

Layers of what look like script in smoky blue, black and yellow jitter across the paintings, evoking both language and the barbed wire that surrounded the camp. In the distance are mountains symbolized by the inverted “W” often used in Japanese calligraphy. Dark and elliptical, they nonetheless illuminate that dark passage in U.S. history. It is as though the paintings are giving up what those tar-paper walls had seen, and it is a whispered tale of secrets, shame and innocence.

Haunting memories—and images—in the making

Similar memories are being created now in the minds of hundreds of undocumented migrant children held in camps at the southern border of Mexico.

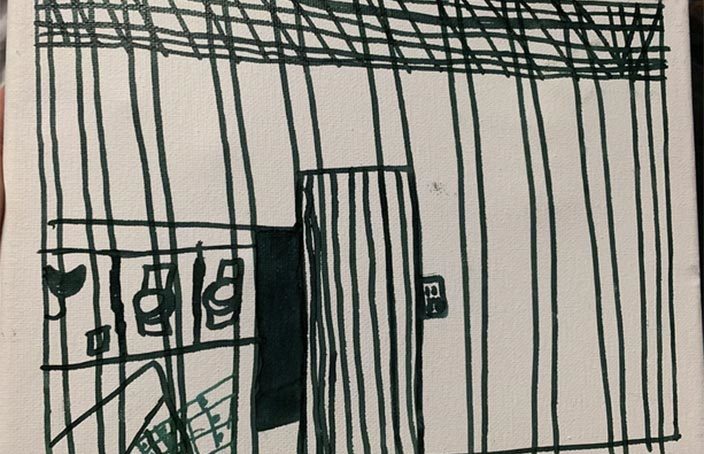

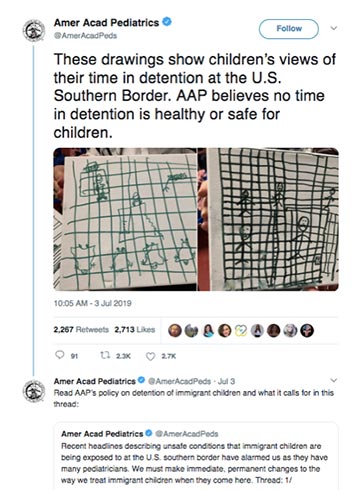

The American Academy of Pediatricians released drawings by children, depicting their experiences as detainees on the border with Mexico

Curators at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History have decided this grim art by children is historically significant. The museum wants to acquire similar drawings and other art by detainees, as a means of documenting this episode of American history.

“The museum has a long commitment to telling the complex and complicated history of the United States and to documenting that history as it unfolds,” the museum said in a statement to CNN. The Smithsonian’s mission seeks to “explore the infinite richness and complexity of American history” and “help people understand the past in order to make sense of the present and shape a more humane future.”

The drawings in question were released by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), as a plea for humane treatment of refugees—adults as well as children. These youngsters created their depictions of their experiences after being released from a U.S. Customs and Border Protection processing center.

“These children coming into our country need a voice,” said Dr. Sara Goza, the incoming president of the organization. “And we will be that voice to try to ensure the right things happen.”

Alone, isolated and idle—no life for a child

Grim as Manzanar was, Towata and his brother had two things going for them that many children at the border now—some of them infants or toddlers—don’t have: The Towata boys were with their mother, aunt and uncle, and they had a certain amount of freedom to roam the camp. The detainees in El Paso have been separated from family members.

Ansel Adams documented the lives of Japanese detainees at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in California (photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Last year, at least 2,700 children—and possibly thousands more—were separated at the border, so that the parents could be arrested under the Administration’s “zero-tolerance” policy. The whereabouts of the children were only “informally tracked” when placed by the Department of Health and Human Services. In April, a federal judge said it may take two years for those children to be identified.

The Trump Administration announced plans earlier this year to house up to 1,400 migrant children at Fort Sill in Oklahoma—the same Army base that once held 700 Japanese-American’s in tents.

What memories will those children have?

Susan Caba, managing editor of American Insight’s FreeSpeech blog, is an independent journalist who covered federal and common pleas courts for the Philadelphia Inquirer. She is the author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Leadership, Fast Track, and writes about politics, popular culture and leadership.