Before America Was America: John Peter Zenger

A map of New Amsterdam, the town that would grow into New York City, 1660.

To the north, the budding city of Philadelphia is just 53 years old, and Benjamin Franklin has recently established the colonies’ first public library. His Pennsylvania Gazette, too, has recently gone into circulation. Little does he know, this will become the most well-known and well-respected newspaper of the Revolutionary War.

The area that will soon be New York City harbors a population that’s growing rapidly, so rapidly that the town has already become the third largest metropolitan center in the British Empire. The United States of America does not yet exist, and it will not for some time. But it’s right here in burgeoning New York City that the country will score its first legal defense of Free Speech.

Upon his arrival in New York City, Irish brigadier-general William Cosby quickly established a reputation as one of the colonies’ most oppressive royally appointed governors. After demanding an increase in his salary, firing Chief Justice Lewis Morris, taking the former governor to court and banning him from ever holding public office in the territory, Cosby’s tyranny received harsh retort from New Yorkers who saw him as an example of typical European royalty.

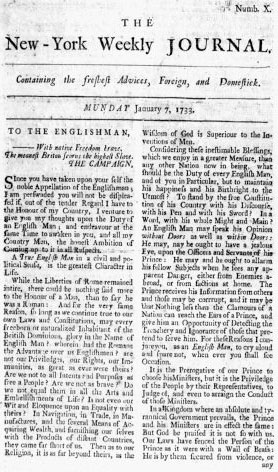

A January 7th, 1733 clipping from John Peter Zenger’s “The New-York Weekly Journal”

John Peter Zenger was a German immigrant whose publication the New York Weekly Journal made no secrets about its desired aims. Its sole purpose was to expose the corruption of William Crosby.

Though the paper’s articles were contributed by Zenger’s peers, they were published by him. Scathing articles accused Cosby of everything from rigging local elections to allowing the French enemy to explore the Hudson River Valley uninhibited.

And so after 2 years of written attacks, Zenger was arrested for libel, an offense that at the time essentially meant publishing information opposed to the government, regardless of whether that information were true or false.

He’d serve 10 months in prison before standing trial, a period during which his wife Anna continued publishing attacks on Cosby’s government.

Standing trial before a jury not of his peers but of members from Cosby’s payroll, Anna’s continued attacks on the government caused such an uproar that fearing a revolution, Cosby had the jury replaced with a jury of Zenger’s peers.

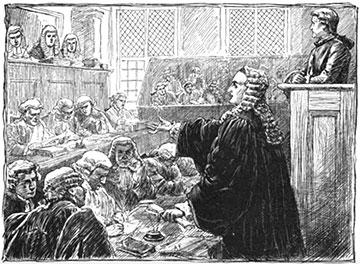

Andrew Hamilton defends John Peter Zenger

It was the face of Andrew Hamilton, a Scottish lawyer on whose behalf the term “Philadelphia lawyer” came to mean a clever attorney.

Hamilton took Zenger’s case pro bono, voluntarily and without compensation. He understood how crucial the case would be in world history.

Hamilton’s defense of Zenger rested with one simple fact: everything published in Zenger’s paper was true, and the jury knew it to be true.

By outlawing the truth, he warned the jury would set a dangerous precedent for communities throughout the colonies. Having come in part to escape the tyranny of Europe, observers and jurors alike understood the implications of Zenger’s case.

Hamilton’s skillful defense of Zenger concluded by saying that the press had “a liberty both of exposing and opposing tyrannical power by speaking and writing truth.”

The case of John Peter Zenger reassured colonists that theirs was a land of complete, uninhibited Free Speech.

To Cosby and the judge, the case was about one newspaper publisher. But to citizens across the colonies, and to the jury, the case was about liberty.

After an estimated ten minutes of deliberations, the jury of Zenger’s peers would find him innocent of libel, forever changing the way average people viewed the concept of libel. A moral precedent was set that truthful statements are legal, even if they criticize the government.

With the landmark decision, freemen throughout the Thirteen Colonies felt a renewed assurance that Freedom of Speech, Expression, and of the Press were all but guaranteed.